|

Discovering the Horses

The Story of the Rescue of the Wilbur-Cruce Colonial Spanish Horse

Text written by Janie Dobrott

© 1996. All rights reserved.

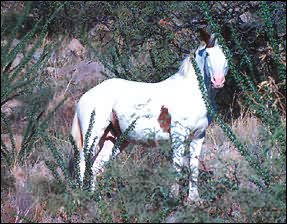

Standing a top a mountain in southern Arizona, catching our breath

from the steep hike, our attention is drawn to a small band of wild

horses grazing far below us. This is what we hoped to see! These

just might be the "horses of History" that we have read about in

the book, "A Beautiful Cruel Country" written by Eva

Wilbur-Cruce, the elderly granddaughter of the homesteader of this

ranch.

Marye Ann and Tom Thompson had driven from Wilcox, AZ to meet us at

the Wilbur Ranch to look at what may be the descendants of horses

brought out of Mexico in the late 1870's from Padre Kino's

headquarters, Mission Dolores. Marye Ann is the registrar for the

Spanish Mustang Registry, and will be able to tell us if these

horses physically fit the type.

After our first glimpse of the horses, we excitedly set off down

the boulder strewn mountain side in a barely controlled slide to

reach the bottom and to get a close look. There, grazing before us

among thorny Ocotillo cactus and prickly Mesquite trees, was a

liver chestnut, medicine hat, pinto stallion and his two mares; one

a chestnut, the other a black. Marye Ann's enthusiasm became

apparent as she led us from one distantly glimpsed horse band to

another until we were caught at dusk with a mountain between us and

our trucks parked at the old Wilbur homestead. Fortunately it was

the fall season, and were were not likely to run into any

rattlesnakes in he dark, as they should have been curled up in

their burrows keeping warm. We followed a deeply cut trail made by

thousands of durable horse hooves, over the mountain, It lead us to

Arivaca creek which was, in times of drought, the only available

water. It bubbled softly by the old adobe walls of the abandoned

Wilbur home.

Back at the vehicles, we recalled what we had seen that day. A band

of "dog soldiers", (old-timer's term for young bachelor stallions),

including a wildly colored pinto, with flaxen mane and tail with a

bald face. A second medicine hat stallion and his two mares; one

bay and the other a pinto. Also, an old grey stallion with a

missing eye, who apparently had lost his mares to a younger,

stronger stallion, and several larger bands with frame overo,

chestnut and bay making up their numbers; some with blue eyes. Could

it be that we had discovered a a remnant strain of Colonial Spanish

Horse? These horses that had been isolated for over 113 years, just

might be the descendants of the horses that... "Padre Kino gathered

from vast herds of Spanish Barbs which had proliferated since the

time of Cortez among the mission farms and ranges in Mexico. Land

which had become fertile breeding grounds for numberless

short-coupled, sturdy, tough horses", (J. Frank Dobie, Horses

and Heroes).

Dr. Phil Sponenberg DVM., representing the American Livestock

Breeds Conservancy and members of the Spanish Mustang Registry,

including Emmett Brislawn,"Doc" Stabler and Marye Ann Thompson,

traveled to the Wilbur Ranch to see the horses in December of

1989. Fortunately for us, the drought had concentrated the horses

along the creek and everyone was able to see a number of horses

without having to hike the mountains. Upon returning,

Dr. Sponenberg wrote his assessment of the herd from which a few

selected quotes have been taken:

The Wilbur-Cruce horses are of a very small handful (five would

be a very optimistic estimate) of strains of horses derived from

Spanish colonial days that persist as purely (or nearly as can be

determined) Spanish to the present day...they are the only known

"rancher" strain of pure Spanish horses that persists in he

Southwest. The Wilbur-Cruce horses are of great interest because

they are a nonferal strain

When comparing the Wilbur Cruce horses to other strains he mentions

that

...they cannot claim the historic isolation that

[these horses] have had... The Wilbur-Cruce horses, as a

nonferal strain, are therefor truly unique. Visual examination of

the Wilbur-Cruce herd indicates that the herd history is very

likely accurate. The horses are remarkably uniform, and of a very

pronounced Spanish phenotype.

My husband, Steve and I lived on the Buenos Aires National Wildlife

Refuge, (adjacent to the Wilbur ranch), at the time of the

discovery of the Wilbur horses in 1989. Steve was the refuge

wildlife biologist and when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

purchased the Wilbur ranch, he became interested in the wild horses

that had to be removed. His reading of Eva Wilbur's book lead him

to contact those who might be able to help identify the horses and

eventually through Marye Ann Thompson and Phil Sponenberg, the

American Livestock Breeds Conservancy was brought into the

picture. Because of Steve's efforts, Eva Wilbur donated her

beloved herd to the ALBC and the Conservancy in turn, through

Phil's efforts, arranged to pay for the cost of trapping, removing

and distributing the horses into breeding groups.

We were in the habit of going over to the ranch to look at the

horses and continue our written inventory in the early summer of

1990. Drought had plagued the area for two years, drying up the

small springs on the south end of the ranch and concentrating the

horses around the two areas of the creek which had not dried up. By

then, the herd which had numbered over 100 head, had become reduced

by mountain lions and rustlers. Once we discovered evidence left by

those who sought to steal for themselves a bit of living history; a

section of fence mowed down by the herd in their panic to evade

their pursuers. Another time we discovered a young foal tied to a

tree with the lasso around its neck that was used to catch it. We

diligently copied the license number of the truck from our hiding

place as we observed those who came back to claim the foal,

throwing it into the back of their camper! They were fined and the

foal confiscated, but by then it was too late to reunite mother and

her offspring.

The young foals also made easy prey for the lions. Over the years,

flash-flooding had cut the banks of the creek 10 to 12 feet high,

which created a vantage point for the lions to perch above the

horses as they come down the tree-lined trails to water. One

weekend we would see a mare with a new foal and the next weekend we

would see the mare with nothing but a swollen udder to comfort

her. The drought also took its toll; the ribs, backbone and hips

jutting out on the mares with foals.

The refuge then hired a man known for his expertise in catching

wild livestock to begin the removal of the horses. The trappers set

up a large pen made up of metal panels adjacent to the old

homestead corral with a water tank in the middle. They then fenced

off the smaller of the two remaining watering holes and staked out

their stockdogs on the one remaining stretch of creek where the

horses could water.

The old corral had been built close to the bank of the creek and in

turn this located the adjacent metal-paneled trap out over the dry

wash of the creek. Towering old cottonwoods, which had undoubtedly

witnessed the original herd drinking under their canopies, lined

the bank here. As the hot days strung out, cicada insects hummed

loudly and and the air seemed to suck the moisture out of every

living thing.

The first horse band to enter the trap included an old, alpha

mare, the only true roan left in the herd, who is now a member of

our breeding group. Eva Wilbur called her "Rosalita", and

remembered her as a foaled the last year she worked and lived on

the ranch.

As the trap filled up with horses, the cowboys herded them into the

old corral, leaving the trap empty and waiting for more. They then

separated the stallions from the mares and foals, whipping up the

dry soil of the corral and creating dust clouds that obscured the

scene from view. Next they were loaded into bob-tailed trucks and

driven to a defunct feed-lot where they were held until the last

horse was caught.

Only one horses was lost during this time. An overo pinto mare

that had and eye with pink skin around it. It was evident that she

had and advanced case of skin cancer and had become weakened and

emaciated from it.

The next move was appropriately to the rodeo grounds of "Old

Tucson", a Western movie set and theme park located just west of

the city. It was from here, that those who were fortunate enough to

receive a breeding group gathered to claim their prize.

Eva Wilbur-Cruce came, despite the heat, to see here equine legacy

dispersed. She arrived wheel-chair bound from a recent stroke, but

attired in her straw hat, sheltered under an umbrella and pleased

to see so many others displaying esteem for the "little rock

horses" that she had lived and worked with for over 60 years.

The temperature that day broiled up to 114 degrees, a recored

setting scorcher! It seemed that a continual intravenous drip would

be the only way to keep our bodies hydrated. It was in this oven of

heat that the vet was scheduled to inspect horses and draw blood

for typing; first stallions, then the dry mares, and then the seven

mares and foals that had survived the lions. They were pushed into

chutes, blindfolded, their markings recorded, and a sticky patch

with a number slapped on their rumps.

Quoting from and article in The American Livestock Conservancy

News, Dr. Sponenberg commented on the bloodtyping:

We held our breath until the results were back, and were

relieved that they were consistent with the history related to us

by Mrs. Wilbur-Cruce. These were indeed purely Spanish ranch

horses, and our efforts were all for the good and worthwhile end of

saving this remnant.

The processing of the horses was finished and now it was up to the

new owners to figure out how to load their wild horses into the

trailers and beat it out of the heat towards Oklahoma, Texas and

California.

Our group of five went with the herd assigned to the Arizona

Pioneer Living History Museum in Phoenix. Because we lived on the

refuge and there had been so much controversy over the removal of

the horses, (some would have liked to see the horses stay in a

group on their historical site) we had to wait to receive

permission to bring our horses home.

We drove the three hours to Phoenix every weekend for the next

seven months to work with the horses. During this time, we used the

"The Jeffery Method" of handling wild stock, as suggested by Phil

Sponenberg. The method consists of catching the horses in a

confined area with a long pole with a noose attached. The handler

then makes "invitational pulls" of the rope, alternating side to

teach the horse to give to pressure and step toward the handler. It

is a slow process, no matter the method, to gentle a wild horse! It

is an experience that taught me much about body language, both

horse and human, and above all to slow down.

Rosalita, (now named Dolores, after Kino's mission), the mare that

Eva had petted as a foal, was gentle enough that we were able to

star her under saddle in August, two months after removal from the

ranch. I rode the mare at the museum's dedication of its new

mission style corral, built for the public display of their

breeding group. Eva Wilbur attended and was able to see some of

what was being accomplished with the horses.

We finally received permission to bring our horses home in January

of 1991. Now we had more consistency in our gentling process. One

memory that stands out distinctly in my mind occurred that spring

after the horses had started to shed. Magdelena, a particularly

sensitive mare, was tied to the fence and I was slowly and

carefully currying loose hair from her back. There was a light

breeze blowing and as I lifted the curry, a around, curry-shaped

patch of hair became airborne and then gently fell to rest on

Magdelena's rump. She startle-jumped a foot upward and I

startle-jumped three feet backward; both our springs were wound

tight that day!

In all the time it took us to gentle our little group, and as

frightened as the horses were in the beginning, not one ever showed

any aggression toward us, never offering to bite or kick. As

anyone knows who has worked closely with this breed, these horses

are as exceptional in their intelligence as they are in their

temperaments.

Since then, Steve and I have moved to New Mexico to manage a large

ranch. The terrain is very similar to that of the home-range of

the Wilbur horses; steep and rock. We are continuing the tradition

of raising the youngsters in rough country, and as they have been

started under saddle, they have proven to be balanced and savvy,

and run with confidence of the rocky hills.

Standing a top a mountain in New Mexico, mounted on a pinto

Wilbur-Cruce Mission Horse, I look out over the grassy valley at

our mares, foals and youngsters. these are what we had hoped they'd

be, "the horses of history", the descendants of the horses that

Padre Kino brought to his Mission Dolores. We are the keepers of Eva

Antonia Wilbur-Cruce's legacy, her beloved "little rock horses",

and it is a privilege.

|